Kireji (lit. ‘cut’ words) are specialist terms used in Japanese haiku which, roughly speaking, have a similar effect to punctuation in English. Rather than beginning with an explaination of what kireji is, let’s have a look at two winter hokku from the poet Mukai Bonen, and simply observe where the punctuation is placed, and how it functions in the poem. I am using winter hokku because here in Aotearoa the rainy season is just getting started, so it feels fitting. I can hear the wind outside, roaring. It’s late, almost 2am, and I have about a third of a mug of genmaicha left, cold but still pleasant . . .

樫の木にたよる山路の時雨哉 kashi no ki ni | tayoru yamaji no | shigure kana oak 's tree <on | rely mountain-path 's | winter rain . . . mountain path sheltered by oak trees . . . winter rain on oak trees the mountain path relies . . . winter shower

からじりの蒲團ばかりや冬の旅

karajiri no / futon bakari ya / fuyu no tabi

light-load 's / blanket <only — / winter 's journey

(on a horse)

traveling light

with only a blanket—

winter journey

A slightly freer translation;

unburdened

just me and my futon—

winter journey

Born in Nagasaki, Bonen came from the well-known Mukai family, and held the offce of machidoshiyori (lit. town elder). He learned haikai from his older brother Kyorai, a prominent Shōmon poet, who was close with Bashō. Bonen's other older brother, Rochō, and younger sister Chine, as well as his extended family like Tagami and her nephew Ishichi, were also involved in the Nagasaki branch of the Shōmon, centered around Kyorai's understanding of Bashō's teachings. Bonen was also skilled in kanshi (Chinese-style poetry).

Kyorai was also responsible for compiling Kyoraishō after Bashō’s death, one of the main sources of information on Bashō’s poetic thoughts and theories today. As I mentioned last week, haiku—descended from the standalone hokku—are poems with 17 kana (i.e. a Japanese ‘syllable’), typically in a 5-7-5 rhythm (but not always), which are required to also contain 1 kire’ji (i.e. cut-word), and 1 ki’go (i.e. season-word). Last week we covered some considerations around kana and form, and next week we’ll cover kigo. But for now, let’s talk about the kireji—

As I said above, kireji are punctive words, which “cut” the poem into two (or more) fragments, as in the Bonen poems above. In Japanese they are voiced, unlike English punctuation which is unvoiced, however they serve basically the same function, which has lead to English-language translators and poets treating them as relatively interchangeable. The two most common English-language “kireji” are the ellipses (...) and the em-dash (—), used either at the end of the 1st or 2nd line. They have the benefit of not being “everyday” punctuation, so retain some of the impact that kireji have in Japanese.

The use of the ellipsis and em-dash in English haiku was derived, in part, from the two most popular kireji in Japanese: kana and ya. “Kana” can be seen in the first of Bonen’s ku, and is always placed at the very end of the poem in Japanese, but typically sits at the end of the second phrase in English. “Ya” is used in the second ku, at the end of the second phrase, though it is just as often used at the end of the first phrase. Neither “kana” nor “ya” have any semantic meaning, and exist purely to “punctuate” the verse.

“Ya” is a kind of hard “cut” or “join” which has been most commonly translated as an em-dash, for somewhat self-evident reasons. “Kana,” as I said above, sits at the end of a Japanese ku, and has the effect of a kind of soft exclamation, which ‘cuts’ or separates out the final phrase from the rest of the verse. As Gabi Greve explains; “By using kana at the end, it might look like one scene/theme/line, but it in fact expresses a juxtaposition/combination of a second scene/theme in the last line.” For this reason, Greve recommends using an ellipses at the end of the second-phrase in English, to achieve a similar effect.

While kireji is traditionally translated as “cut-word” (kire = cut, ji = word), and this is certainly valid, I have always preferred the term ‘pause-word’, as used by Nippon Gakujutsu Shinkokai team in the handbook, Haikai & Haiku (1958), or ‘join-word’ (derived from the term “ku'gire” used to describe the ‘pause’ in tanka). The term ‘cut’ in English carries with it a certain expectation of shock: a jolt, a fissure, a rupture, and so on. However, the term ‘kire’ in Japanese refers not only to sharpness and cutting—from the verb kiru (to cut)—but also means ‘pieces’, ‘fragments’, or ‘strips’, particularly in reference to the ‘scraps’ of cloth left over from embroidery and sewing (and can simply mean ‘cloth’ in some contexts). In sewing, “cutting” is transitory, an action rather than a result—a “cut” is made only so that the ‘cuttings’ might be sewn back together—transforming the ‘cut’ into “folds,” “seams,” and “pleats” (etc.).

Focussing on the term “cut” in English discussions has tended to limit the potential of haiku discursively: cutting it off at the feet, so to speak. Bashō used the term toriawase to describe the essence of kireji, meaning an ‘assortment’ or ‘assemblage’ (lit. “to take together and join”), containing a vast range of possible effects and affects, including but not limited to: linkages, likenesses, combinations, comparisons, contrasts, joinings, juxtapositions, and so on. However, in English “cutting” is overwhelmingly understood in terms of ‘contrast’ and ‘juxtaposition’ alone, which again has tended to limit the potential range of linguistic effects and affects it opens onto. For instance, in this hokku of mine, there is no “juxtaposition”, rather the kireji works to join the disparate images together, fusing them into a kind of meta-simile;

like a poem

swollen with rain . . .

earthworm

Okay, that’s it for now. We’ll pick up again next week with some discussion around kigo. As always feel free to leave comments in poetic form—especially haiku. While we could spend all day talking about poetic technique, at the end of the day the best way to learn is by doing. Have a great week!

xoxo

dw

Haiku Thursdays

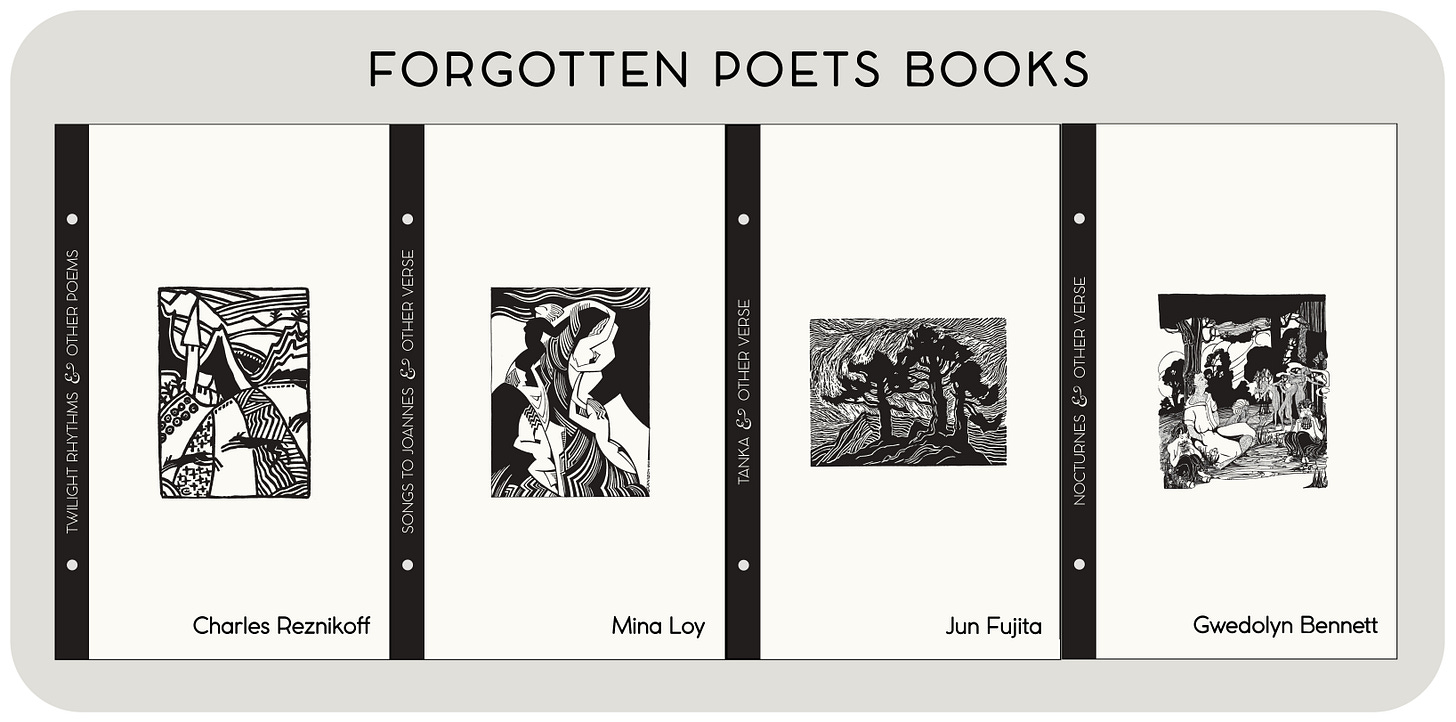

Notes for an unfinished miscellany on haiku in English, including poems, translations, histories, theories, et al. Explore the archive . . .

Haikai & Haiku—A Short Introduction Part 1: Kana

Today I would like to discuss the form of haiku, using a hokku by the poet Ajō as a starting point. The term “haiku” was not in common use prior to the 1900s, but the form of poetry it referred to—i.e. a verse containing 17 kana, in the rhythm 5-7-5...

Haikai & Haiku—A Short Introduction Part 3: Kigo

There are three fundamental aspects of haiku: kana, kireji, and kigo. Last week we discussed kireji (i.e. cut/join words) and the week before that we discussed kana (i.e. syllable counting and form). This week, we are going to discuss the third, and final, aspect: kigo...

Haikai & Haiku—A Short Introduction Part 4: One Plum Slowly Ripens

Most Westerners are taught in school that haiku are poems comprised of 17 syllables, arranged over 3 lines, with 5 syllables on the first line, 7 syllables on the second, and a final 5 on the third (5-7- 5). There are two problems with this definition, which need to be addressed by anyone wishing to translate haiku, or write haiku in English...

I like your haiku best!