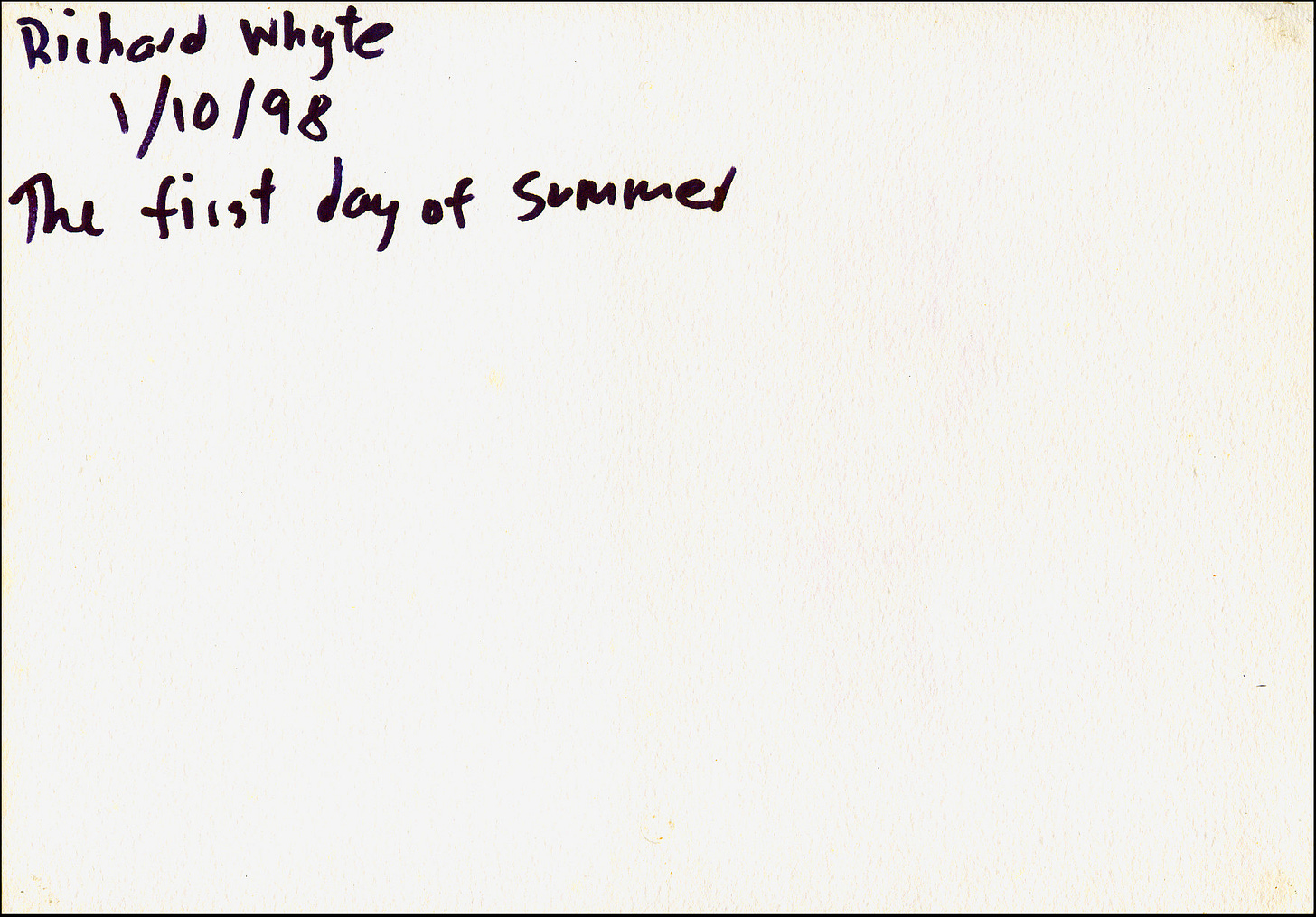

1998-1999 were the first years I considered myself an “artist” (ironically, a word I have come to dislike, haha). A lot of what I did then is lost now, and with good reason—it was bad! However, I did make a catalogue of my favourite works from late-1998 through 1999 for a university course I was doing, which I came across in an old box the other day. The 42 works listed include music, paintings, prints, short films, photocopy art, readymades, installation works, conceptual ideas, and performances, excerpts from a cut-up prose work, a few poems, and the first drawing I ever did (still one of my favourites);

According to the catalogue notes, typed up on an old manual typewriter: “Reading Beyond Painting (Max Ernst) and The New York School (Dore Ashton), drinking black coffee and learning to smoke cigarettes (that comes later)… seeing Goddard in Soigne ta Droite (remembering A Bout De Souffle) and writing haiku (a version of our own).” How strange. I genuinely had no idea that I called these poems ‘haiku’ at the time—I had been under the impression that I came across haiku many years later. Memory is a funny thing.

The contents page of the “catalogue” says I wrote 10 haiku in late-1998, and they are likely the first ‘poems’ I composed as an adult. I could only locate 5 of them, and I only like 3 enough to share;

3 Haiku by Dick Whyte 6.10.98 tiredness in our eyes then words 20.10.98 outside sitting rain, smoke and memory Oct. 1998 to wake beside you is all . . .

I wonder where I learned about haiku? I don’t think it was in high-school? Maybe I got it from Kerouac or Ginsberg? I have a memory of hitching somewhere with a friend, and coming across a book which had a definition of haiku in it. I remember writing it down in my notebook. But I don’t remember what it said. Or when it was? If I was to publish these today, I think I would probably edit them together into one poem. Maybe something like;

tiredness in our eyes then words, outside sitting rain, smoke and memory— to wake beside you is all . . .

It’s not a great poem, by any means, but I am really thankful to be able to look back on these fragments of the past. I thought I had lost all my poems from this period! At the time, my favourite book of poetry was Samuel Beckett’s Poems in English (1963), which I read and re-read, over and over. I don’t think I read any other poetry back then, but I liked Beckett’s novels so I picked it up. I don’t know what happened to that book—I no longer have it—but I ended up using my favourite poem as a title for both a short-film, and a painting;

Trois Poèmes III by Samuel Beckett I would like my love to die and the rain to be falling on the graveyard and on me walking the streets mourning her who thought she loved me

The verses in Beckett’s Poems In English were originally composed in French, which Beckett then translated into English. This fascinated me at the time. As Beckett explains; “More and more my own language appears to me like a veil that must be torn apart in order to get at the things (or the ‘nothing-ness’) behind it. Grammar and Style. To me they seem to have become as irrelevant as a Victorian bathing suit… A mask…Is there any reason why that terrible materiality of the word surface should not be capable of being dissolved?” (in a letter to Axel Kaun, 1937) He then experimented with writing in French; “Because in French it is easier to write without style.” Here’s the original;

je voudrais que mon amour meure qu’il pleuve sur le cimetière et les ruelles où je vais pleurant celle qui crut m’aimer

Doing a little research today, I found out that the version I knew was the third translation Beckett did of the poem. The second was almost identical, with ‘sought to love me’ in place of ‘thought she loved me’. The first (published in 1948) had an entirely different last-line in English, which, all these years on, I much prefer to the later versions;

I would like my love to die and the rain to be falling on the graveyard and on me walking the streets mourning the first and last to love me

There is only one other poem included in my “catalogue,” used as a ‘description’ of one of the conceptual sculptures;

View from Semeloff Tce. 24.4.99—7.40pm by Dick Whyte deep blue night— illuminating clouds— a calm tension— floating—

Alongside a fragment which isn’t numbered, included in the contents, or attached to any other works, which I think is the best of my early ‘poems’;

April 1999 by Dick Whyte space: a receding sky a plain of colour an empty carpark a night together

I often felt a bit hoarder-y holding on to all this stuff. Who cares, right? I’ve culled a lot of rubbish over the years—usually between moves—but kept most things that could roughly be called ‘art’ in some form or another. Today, I am really glad I saved a bunch of things. It is amazing to look back and see poems I wrote 25 years ago, and not hate them. They may not be my favourites, but I am not embarrassed by them, in the slightest.

It’s also really interesting to me (and probably me alone, haha) that my earliest poems display all the same concerns as my poetry today: brevity, compression, and fragmentation. It would take me many many years to consciously understand this about my poetry. But now I see that from the very first poems I wrote, these three concepts were already front and centre. I hadn’t realised that. Concepts I am still grappling with, and figuring out.

And this is what we call style in poetry, right? Understanding these kinds of things about our own work, I think, can allow us to develop a deeper understanding of our relationship with style. It can also allow us to change our approach to style, or freshen it up, because we can become aware of it, rather than being locked into it unconsciously. In this sense, making things, and then looking back on them stops being a process of ‘judgements’ (which tends to focus on past works as ‘being’ either ‘failures’ or ‘successes’), and instead turns into an ‘experiment on the self’ (how am I altered by making, in a constant process of ‘becoming’; how am I both staying the same and changing?).

How are we, as poets and makers, endlessly changed by the act of writing poetry, or making things? How can we appreciate these changes? Nourish these changes? And eventually, be more conscious of who we were, to be better informed about who we would like to become? Which leads me to a question for you, dear readers. Do you have any poems from your early days that you’ve held on to? Do they teach you anything about the poet you are today? What would you say to that younger poet? What would they say to you? If you’re feeling reflective, hit up the comments section, I’d love to hear about it!

Till next time,

xoxo dw

Vespers

Poems by Dick Whyte, and other miscellanea. Explore the archive . . .

My First Poetry Book Vol. 1: Very Short Poems (2000-2001)

as the cat from next door sleeps calmly, candle wax collecting on paper...

My First Play & Some Pictures (1999)

Untitled #1 Fade up on someone sleeping in a bed. A voice: alone (pause) perhaps alone (pause) although (pause) not entirely...

My First Abstract Short Films (1999)

These films use a technique called ‘video feedback’ in which a camera is hooked up to a television display, and then pointed back at the television, effectively seeing itself...

Love how you combined those 3 haiku to form a poem, they work beautifully together. I've recently exported all my writing from another website. Flicking through 100 poems and I still don't think I've found my own style.

Really enjoyable reflection, Dick. Beckett’s comment about ripping the veil of the temple out of language (alluding to the Passion) must have Nietzsche in mind: “I am afraid we are not rid of God because we still have Grammar”. I share your dislike of the word artist btw haha (or at least its casual use). But to your question. Some years after I left university my parents asked me what to do with my clunking old computer still lodging with them. It had all my undergrad poems on it, I thought for a moment and then decided - throw it out. Except in odd moments of nostalgia I don’t regret that - the poems were bad - though reading your youthful work (which I like) I wonder if there might not have been something salvageable there. I believe there is a poem from a still earlier stage, my teen years, in a school magazine somewhere... perhaps some time I’ll try to look it out...