In Back to Beginnings Parts 1-3 we discussed chōka, tanka, katauta, and seodōka. Of these three tanka (lit. ‘short verse’) was widely popular throughout Japan as early as 500 CE, and would go on to become the primary poetic form for the next 800 years or so. It was revived in the late-1800s, and by the mid-1900s would become popular throughout the world. In this part we are taking a closer look at one of the oldest surviving tanka handbooks from the 700s, from which can be derived not only the fundamentals of tanka, but of short poetry in general. It also briefly covers chōka, katauta, and sedōka, so helpfully acts as a summary of everything discussed in the last 3 parts. Enjoy!

“I have prepared a volume titled Uta no Shiki, in which I have set down the new rules of poetry illustrated with poetic excerpts. Surely those who recite these poems will avoid giving offence, and those who hear them can take counsel.”

Fujiwara no Hamanari (c. 724-790) compiled the earliest surviving text of waka (i.e. tanka) criticism sometime before 772; “A courtier of middling rank, then serving as Minister of Justice and Court Consultant” who “was commissioned by Tennō Konin to compile Uta no Shiki (lit. 'Poetic Styles').”1 While the final date of compilation falls after that generally given for the Man'yō'shū (c. 759), the writing of Uta no Shiki probably predates this by a number of years. Of the 34 poems cited by Hamanari, 15 are similar to verses quoted in the Man'yō'shū, and 3 to verses in the earlier Koji'ki (c. 712) and Nihon'shoki (c. 720).2

Instead of

saying clever things,

drink sake

get drunk and have a cry,

wouldn't that be best.

—Ōtomo no Tabito (c. 665-731)3

Hamanari begins by identifying the origin of poetry in its ability to “stir the innermost feelings of the spirit, and soothe the passionate hearts of people and kami alike.”4 This sentiment runs throughout the history of uta and waka, and is repeated 150 years later, almost word for word, in the introduction to the Kokin'shū (c. 905), the first of the Imperial anthologies of tanka; “It is poetry, which moves the skies and the earth, stirs the feelings of the invisible spirits, and smooths the relations of people.”5 However, unlike the Kokin'shū, Hamanari's critique does not go on to describe the actual state of waka at the time, but instead prescribes a “new” approach, modelled on a Chinese poetics of rhyme;

“In recent times, poets have shown excellence in versification, but they seem to know nothing of the use of rhyme. While their verses may bring pleasure to the reader, they have no knowledge of ‘poetic defects’. How can poetry stir the feelings and soothe the hearts of people and spirits, if it is not written in the 6 Chinese modes?”6

The rest of Hamanari’s text is organised into 3 sections, outlining various “styles” of poetry, with examples and discussion. The first 2 sections address styles which are 'poetically defective' (i.e. things Hamanari thinks poets shouldn't do – firstly within rhyme, and then in general), while the last addresses styles that are 'poetically desirable' (i.e. things he thinks poets should do). In this sense it is a moralistic analysis. Thankfully, Hamanari's vision had little impact on the practice of waka, and rhyme never became a dominant force in Japanese poetry.7 Because of this, Uta no Shiki is “remembered more as a historical curiosity than as a practical guide to poetic composition.” However it is clear that Hamanari's overview draws on ideas from earlier waka treatises, none of which, one imagines, had anything to do with rhyme. Perhaps then, by carefully accounting for Hamanari's idiosyncrasies throughout the text, some of the source material might be extracted from the discussion, giving us something closer to the kind of waka manual used by poets at the time?

In the future will people remember me too, yearning for the past as is the heart's way?

—Fujiwara no Shunzei (1114-1204)8

For instance, Hamanari argues that there should be 3 basic styles of poetry: 1) Kyūin ('rhymed', i.e. 'regular' style), 2) Satei (i.e. 'irregular styles', including a sub-category of 'unrhymed' poetry, among others, which he considers 'defective') and, 3) Zattei (i.e. 'miscellaneous styles', which are 'desireable').9 By simply swapping 'unrhymed' (which now becomes the 'regular' state of waka) with 'rhymed' (which now becomes an 'irregular style'), it is possible to arrive at a much clearer picture of waka theory at this time: 1) Riin'tei (i.e. 'regular unrhymed styles'), 2) Sa'tei (i.e. 'irregular styles', now including 'rhyme'), and 3) Zat'tei (i.e. 'miscellaneous styles'). Similarly, rather than following Hamanari's arrangement of the 'styles' according to moralistic 'defects' and 'desires', they can be rearranged according to Hamanari's descriptions, providing a more pragmatic set of concepts from which to begin a discussion of waka poetics, and the short poem in general.

— Riin'tei —

REGULAR STYLES

Of the 'regular' (now, unrhymed) styles, Hamanari identifies 4 basic patterns – chō'ka, tan'ka, kata'uta, and sedō'ka: 1) Chō'ka (lit. 'long-verses') are composed in pairs of phrases, in alternating 5-7 couplets (i.e. 5-7 + 5-7 + 5-7, etc.), for as long or short as the poet wishes, concluding with a 3-phrase triplet 'base', in the pattern 5-7-7 (i.e. 5-7 + 5-7 … + 5-7-7).10

Eating melons I think of my children, eating chestnuts I miss them even more, from where do these thoughts come, before my eyes lingering so uselessly, unable to sleep in peace.

—Yamanoue no Okura (c. 660-733)11

2) Tan'ka (lit. 'short-verses') then, are simply the shortest possible chōka, comprised of just 5-phrases: a single 5-7 couplet, combined with a 5-7-7 'base' (i.e. 5-7-5-7-7).

Living in this world, to what can it be compared? At daybreak a boat rowing away leaves no trace.

—Priest Manzei (c. 720)12

The common building-block of these styles, which Hamanari calls the 'base' or 'foundation' (moto), was also known as, 3) Kata'uta (lit. 'incomplete-verse'), typically written in triplets of 5-7-7 (i.e. the bottom of a tanka, the final stanza of a chōka).13 Hamanari also identifies 2 other possible styles of kata'uta (i.e. 'fragment-verses'): 1) Yūtō'mubi (lit. 'head-without-tail', i.e. verses comprised only of the 'head' of a tanka, in 5-7-5, which would much later become the hokku, and then haiku), and 2) Mutō'yūbi (lit. 'headless-with-tail', a mostly theoretical 4-phrase verse form, in 7-5-7-7).14

This pear tree if planted and grown, how awesome.

—Yasaka no Iribime (c. 50 CE)15

4) Sedō'ka (lit. 'head-spinning-verse'), are comprised of a pair of katauta (2 'bases', one after the other), producing a 6-phrase verse (i.e. 5-7-7-5-7-7).16

White clouds hanging over the mountain, I never get tired of the view! If I was a crane, I'd soar over in the morning and not return until evening.

—Ōmiwa no Takechimaro (c. 657-706)17

Of the 'regular styles' only a few hundred chōka, 60 or so sedōka, and a handful of kata'uta have been preserved, and none appear to have been composed regularly after the 9th century.18 Tanka, on the other hand, became overwhelmingly popular, with more than 30,000 examples being collected throughout the 21 volumes of the Chokusen Waka'shū (Imperial Poetry Collections, c. 920-1440 CE).19 Most of Hamanari's remaining 'styles' are largely variations on tanka, rather than chōka or sedōka, though it would be reasonable to assume that anything said in tanka's defense, could be reliably applied to the other 'styles' as well.

— Sa'tei —

IRREGULAR STYLES

We can begin Hamanari's discussion of 'irregular styles' with: 1) En'bi (i.e. 'monkey-tail'; in which the tanka's final-ku is short by a few kana), and 2) Restsu'bi (i.e. 'extended-tail'; in which the tanka's final-ku is slightly long).20 These 'styles' speak to the regularity with which any ku – in tanka, haikai, or otherwise – might be a few kana short or long, depending on the needs of the poem. And certainly, looking at the examples of poetry preserved from this period, it is safer to say that composing in patterns of tan'ku (i.e. 'short-phrases') and chō'ku (i.e. 'long-phrases') was the 'rule', and that the rhythm of 5 and 7 kana was more a 'recipe', than 'requirement' (a poetic formality, rather than a 'form' of poetry, in the Western sense of the term).21

As the rooster's crow signals dawn, Night brightens into day amid the sound of temple bells at play.

—Eguri no Toshima (c. 700s?)22

In place of 'unrhymed' verse, 3) Kyūin (lit. 'rhyming' verses) can now be included as an 'irregular style'. While Hamanari's prescription for 'regular rhyme' in tanka (i.e. at the end of the 3rd and 5th-ku, as above) never became popular, in practice, this should not be taken to mean that waka never used rhyme. Of course poets played with 'sound' in relation to rhythm, which included features of 'rhyme'. However, regular patterns of end-rhyme would never become a defining feature of waka, unlike Chinese-language poetics, for instance, in which 'rhyme' played a significant role, or pre-1900s English-language poetics, in which 'end-rhyme' was effectively synonymous with the general definition of 'poetry'.

Bright, bright! Bright, bright, bright! Bright, bright! Bright, bright, bright! Bright, bright, moon!

—Myōe (c. 1173-1232)23

Within 'rhyme', we might also include one of Hamanari's 'miscellaneous styles', known as: 4) Shū’chō (lit. 'clustering butterflies'), a 'style' of rhymed-tanka in which every ku begins with the same word, as in Myōe's highly 'irregular', but effective, tanka above.24

— Zat'tei —

MISCELLANEOUS STYLES

After discussing 'irregularities' within waka composition, Hamanari moves on to discussing those styles he finds particularly pleasing. Significantly, the 'highest order of verse' for Hamanari is, 5) Kenkei (i.e. 'puzzle-verse'): waka written in 'code', needing to be 'solved' like a 'riddle'.25 Hamanari gives one of his own tanka as an example, in which each of the 5 phrases is a literal riddle, spelling out the solution line by line (one part 'crossword', one part 'acrostic'). In practice, 'puzzle-verses' of this type are relatively uncommon, and reflect Hamanari's idiosyncratic tastes. Here is a much later example;

A two-part-letter => こ ko

then a horn-like-letter => ひ i

a straight-letter => し shi

and then a bent-letter! => く ku

I think about you. <= Yearningly!

[koishiku]—Yoshida Kenkō (1283-1350)26

At the same time, Hamanari's general explanation of kenkei as verses “in which the poet expresses their feelings in veiled terms” suggests a much broader scope, capable of encompassing a whole range of 'indirect' styles of expression (i.e. figurative-language; allusions, allegories, analogies, metaphors, metonyms, similes, etc.). In this sense, kenkei could be read as a prototype for those more lateral styles found in the Man'yō'shū, such as hiyu'ka (lit. 'comparison-verses', i.e. 'metaphor', etc.) and kibutsu'chinshi (i.e. mono no yosete omoi o noburu, lit. 'expressing thoughts indirectly through things').27 These threads are later picked up by Ki no Tsurayuki in the introduction to the Kokinshū, and recast into 6 'poetic principles', half of which directly concern the use of veiled-speech: 1) Soe'uta (lit. 'indirect-verses', i.e. in which 'the surface meaning of the poem conveys an unrelated hidden meaning'), 2) Nazurae'uta (lit. 'allusive-verses', i.e. poems of 'likeness' and 'comparison'), and 3) Tatoe'uta (lit. 'figurative-verses', i.e. poems using 'evocative imagery').28 Much later, similar ideas would be applied to haikai and haiku, as in Bakusui’s theory of “shapeless feeling.”

A trail of clouds from the River Sawa to Mount Unebi, the trees are rustling the wind about to blow.

—I'suke'yori'hime (c. 585 BC)29

On the surface, this tanka by I'suke'yori'hime can be read as a descriptive-verse, in the form of a 'landscape'. However, it was also used as a literal 'coded' message, through which I'suke'yori'hime was able to inform her 3 youngest children of their elder-brother's plot to murder them: the wind about to blow. As a result, they were able to avoid death, and Tagishi'mimi met his fate instead. Literally, the poem is a robust natural vista, contrasting the magnitude of the clouds reaching across the plains and the miniature of the rustling trees, with the anticipation of the wind, producing an equivalence between the elements: pushing clouds and felling leaves, as if they were the same thing. Laterally, the poem functions as a metaphor, or allegory, for 'veiled feelings'. Importantly: these two functions are not opposed to one another. Unaware of the lateral dimensions of the poem, it can still be enjoyed literally, as a richly layered landscape-scene.

Tenderly the tender grass within the reed fence, if you smile at me like that people will know!

—Anonymous (p. 759)30

Alongside 'veiled-verses', there are numerous styles defined by their unveiled (i.e. 'direct') language. In the Man'yō'shū, for instance, eibutsu'ka (lit. 'poems-about-things') and seijutsu'shinsho (i.e. tada ni omoi o noburu; lit. 'expressing thoughts directly') both rely on saying what they mean. Similarly, the principle of kazoe'uta in the Kokin'shū (i.e. 'descriptive-verses', in which 'things are described as they are without analogies') also sits with in this tradition.31 Of course, such verses aren't “devoid of imagery [and] in practice there is considerable overlap” with those poems belonging to the lineage of 'veiled-verses'.32 In this sense, when Hamanari writes that kenkei is the 'highest order of verse', he is aligning it with 'poetic speech' in general, as the base (moto) technique of waka. This can be contrasted with, 6) Jikigo (lit. 'plain-speech').33

In a dream the plum-blossoms whisper; “Don't just leave us to fall, let us float in the sake.”

—Anonymous (c. 700s)34

If we can consider ken'kei Hamanari's 'ideal' for poetic-speech, its failure becomes: 7) Ri'kei (lit. 'incongruous combination' of ideas, etc.), in which the various phrases are 'jumbled' and 'confused', as if “cows, horses, dogs, mice, and the like were huddled together in one place. There is no elegance in this.” For Hamanari the best poetry is always a puzzle of sorts. However, if the poet makes the puzzle too obscure, or cloudy, the verse will end up 'jumbled', and the reader won't be able to make heads or tails of it. On the other hand, if the 'puzzle' is already solved for the reader, and too clear, the poem may lose its depth, and become an entirely different kind of 'jumble'. As with all things poetic, while “incongruous combinations” may be a deficit much of the time, in various kinds of “nonsense” verse it is a highly desirable quality, as found in styles like mushin shojaku no uta (i.e. kokoro no tsuku tokoro naki uta; lit. 'without-mind-verse'), in the Man'yō'shū.35

Memories surface, on an evergreen mountain wild azaleas, if I don’t say anything it is because I love you.

—Anonymous (c. 800s)36

To finish this section, Hamanari discusses various styles of poetry in relation to their usage of language across time. Fleshing out Hamanari's analysis slightly, we can probably agree that various styles of language used 'now' (i.e. the 'present') will differ, in some way or another, from various kinds of language used prior to 'now' (i.e. the 'past'). Simply put, styles in language change over time. Language that feels ‘of the past’, Hamanari calls, 8) Kojii (i.e. verses using 'old figures of speech', in distinction to 'present speech').

Similarly, within any 'contemporary' uses of language there are certain styles of speech (particularly in poetry) which feel not of the 'now', but distinctly 'novel' (i.e. 'new', of the 'future'), which Hamanari calls, 9) Shin'itei (i.e. verses using 'novel expressions'). If poets 'overuse the traditional' they can end up sounding 'excessively mannered', but at the same time, if they 'experiment too boldly' they may risk falling into 'jumbled-expression'.37

Drink this fresh sake of the gods they said, that must be why I've gotten so drunk!

—Urabe Drinking Song38

Rather than using a prescriptive model to define the two styles, Hamanari uses a productive model to divine a number of new styles, through various combinations: 14) Tōko'yōshin (lit. 'old-head-new-waist'; with 'old speech' in the head, and 'novel speech' in the waist), 15) Tōshin'yōko (lit. 'new-head-old-waist'; re-versing of the previous style), and 16) Tōko'yōko (lit. 'old-head-old-waist'; in which the entire tanka is comprised of an 'old figure of speech').39

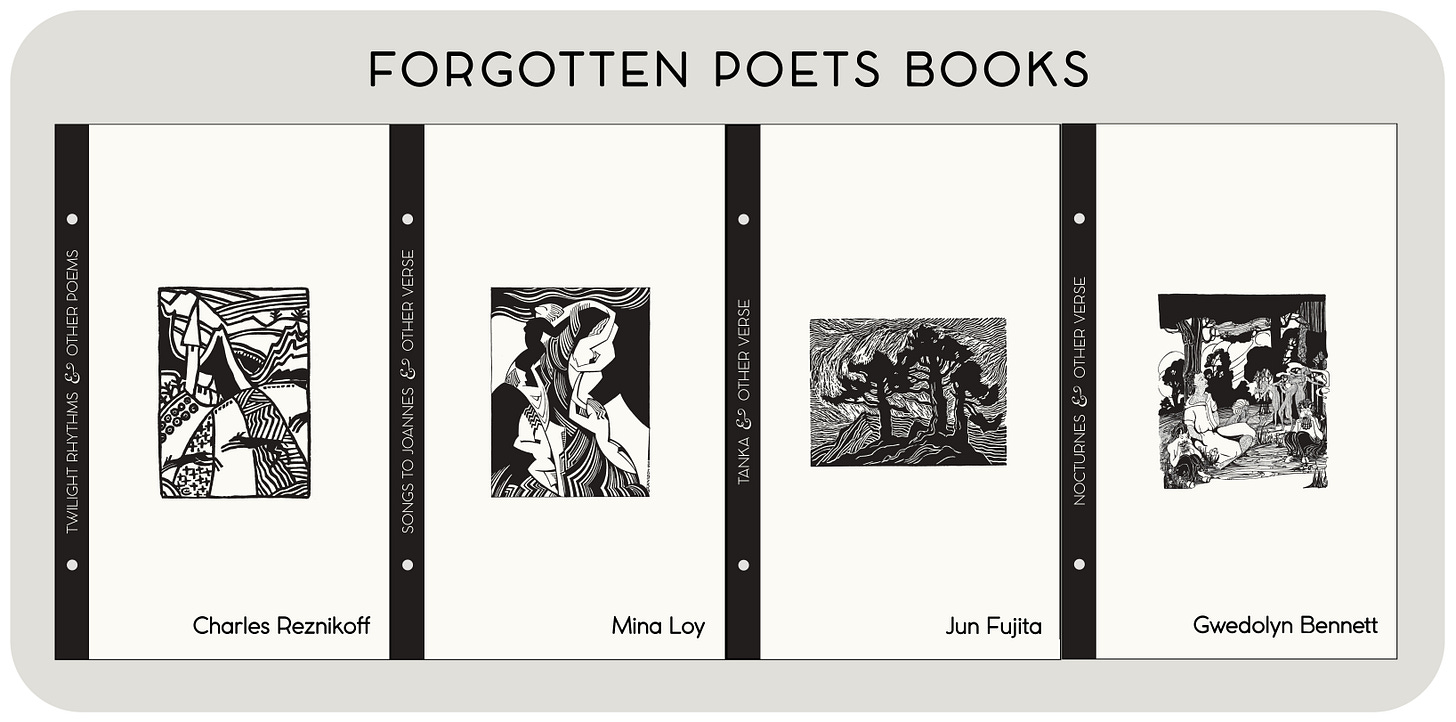

Whew, okay, that’s it for this weeks Haiku Thursdays, and that’s probably it for the Back to Beginnings series for the next little while. While tanka would go out of fashion in the 1500s and 1600s as haikai and hokku rose to prominence, it would be revitalised in the late-1800s and early-1900s by poets like Masaoka Shiki, Takuboku Ishikawa, Akiko Yosano, Akiko Yanagiwara, Takeko Kujō, et al. Not long after this it would go on to become a popular form in English, through the work of Japanese-American poets like Yone Noguchi, Sadikichi Hartmann, and Jun Fujita, and was particularly influential on ‘new verse’ poets like Adelaide Crapsey, Amy Lowell, John Gould Fletcher, and Witter Bynner, et al. But these are discussions for another time . . .

As always, whether you are new to tanka, or a seasoned pro, I’d love to read some poems in the comments! My own tanka journey started in 2008, after getting a translation of Takuboku Ishikawa’s tanka collection Sad Toys. So, to round things off, here are a few of those early efforts;

Tanka by Dick Whyte * learning to write tanka on the plane— my lips dry out while Takuboku's pages curl * drip! drip! drip! after the rain an old tin can makes a fine drum * cars drift through the valley— exhaust fumes mingle with bird song * walking to the shop i make a list— car, tree, ant, house, road

Rabinovich, Wasp Waistes and Monkey Tails: A Study and Translation of Hamanari's 'Uta no Shiki', p471. Also known as Kakyō Hyōshiki. This section of the text is based on a close reading of Rabinovich's translation of Hamanari.

Furthermore, “only 5 of these are identical. Moreover, just 5 of these 15 similar verses are attributed to the same poet in both texts, further suggesting that Hamanri did not utilize the Man'yō'shū as a source.” (Rabinovich, p481)

Man'yō'shū, Book 3, Poem 341 (Nippon, M, p117; Shirane, TJL, p100-4). From, '13 Poems in Praise of Sake'.

Tr. Rabinovich, p526.

Kokin'shū, 'Kanajo Preface' (tr. Rodd, p35).

Tr. Rabinovich, p527.

Fujiwara no Shunzei (c. 1114-1204), for instance, “wrote briefly about poetic defects and the use of rhyme in his treatise on poetry, Korai Fūteishō (c. 1197-1201).” While acknowledging Uta no Shiki “as the first poetic code,” and noting that “some people had advocated the use of 'rhyme words' (in no ji) in chōka and tanka,” Shunzei maintains, reflecting poetic practices of the time, “Rhyme has no real [i.e. 'regular'] place in waka.” (Rabinovich, p517)

Shin'kokin'shū, Book 18, Poem 1845 (tr. Rodd, p748; Jin'ichi, HJL Vol. 3, p73; Royston, The Poetic Ideals of Shunzei, p1). With the head-note; “Looking at verses of old, when selecting waka for the Senzaishū.” (Rodd, p748)

Rabinovich, p540-41.

For Tachibana Moribe (1791-1849), chōka themselves also come in 3 varieties, determined by the overall number of ku: “those consisting of 7-15 ku are shō'chōka (lit. 'little-chōka'), those ranging from 16-50 ku are chū'chōka (lit. 'middle-chōka'), and those consisting of 51 or more ku are all dai'chōka (lit. 'large chōka').” (see Thomas, Sound and Sense: Choka Theory and Nativist Philology in Early Modern Japan and Beyond, p11)

Man'yō'shū, Book 5, Poem 802 (Shirane, TJL, p64-5; Cranston, GGC, p352).

Manyōshū, Book 3, Poem 351 (Nippon, M, p237; Carter, TJP, p2 & 51; Cranston, GGC, p340-1).

For examples, see: Kojiki, tr. Chamberlain, p266-269. For discussion in the context of Japanese poetics, see: Yasuda, TJH, p109-10. Chikara Igarashi (1924): “The four great forms – namely katauta, sedōka, tanka, and chōka – whose essence is based on the 5-7-7 form.” (Yasuda, p114)

Rabinovich, p543-44; Yūtō'mubi and mutō'yūbi are the 3rd and 5th of the 'irregular styles'. Though a 4-ku style known as dodoitsu, written in 5-7-7-7 would become popular in the mid-1800s, fulfilling Hamanari's pattern.

Uta no Shiki, Poem 21 (Rabinovich, p544).

Rabinovich, p548. Clearly the 'head' referred to in sedōka is the head (i.e. mind) of the reader, rather than the 'head' (i.e. the upper 5-7-5 section) of the tanka, in Hamanari's terminology. This may explain why Hamanari uses the term hita'moto (i.e. 'repeating-base' verse), drawing on sō'hon'ka (lit. 'added-base-verse'), rather than the more common sedōka, when discussing this 'style' (to avoid confusion).

Uta no Shiki, Poem 26 (Rabinovich, p548). To retain Hamanari's sense of rhyme: 'I never get tired of looking!'.

There was, however, a revival of interest in chōka in the Edo Period, beginning with poets like Kamo no Mabuchi (1697-1769), “who more than anyone else added momentum to the fledgling revival of chōka composition, [and] also wrote what could be seen as the first attempt at poetics for that genre.” Later, “choka poetics was developed by three major theorists over the first-half of the 19th century: Oguni Shigetoshi (1766-1819), Tachibana Moribe (1791-1849), and Mutobe Yoshika (1798-1863).” (Thomas, 'Sound and Sense: Chōka Theory and Nativist Philology in Early Modern Japan and Beyond', p10) At the same time there was also revived critical interest in kata'uta and sedō'ka, and their role in the history of waka poetics. (see Yasuda, TJH, p109)

Alongside the Man'yō'shū and the Chokusen Wakashū, the original “Kokka Taikan (i.e. 'The Great Canon of Japanese Poetry', c. 1901-02) and its supplement Zoku Kokka Taikan, contain nearly 85,000 waka, and that is the merest tip of the iceberg.” (Royston, 'Utaawase Judgments as Poetry Criticism', p100)

Rabinovich, p542-43; Enbi and retsubi are the 2nd and 4th of the 'irregular styles'.

Yasuda: “Historically speaking, it cannot be said that there was a clearly formalized, rigid adherence to each of the verse patterns. Although the rhythm is basically in a 5-7 pattern, it was as honored in the breach as it was in the observance, and poems were written... with great latitude as regards form. Of them, only tanka retained its poetic [regularity] fairly consistently.” (TJH, p114-5) Still, ji'amari (lit. 'too-many-kana', i.e. hypermetric ku, as well as hypometric ku) were not necessarily considered 'defects' or 'faults', and some styles even encouraged them. In kyōgoku, for instace, an approach to tanka popularised by Fujiwara no Tamekane (c. 1254-1332), ji'amari was 'one of the most prominent characteristics' of the school. (Cranston, 'Waka Wars', p450)

Uta no Shiki, Poem 20 (Rabinovich, p548).

From Myōe Shōnin Wakashū (c. 1248), a collection compiled by Kōshin, one of Myōe's students, based on Myōe's own Kenshin Wakashū, with various additions from his uncollected works. This poem was one of the additions: “Because of such a spontaneous and innocent stringing together of mere exclamations as this, Myōe has been called the poet of the moon.” (Yasunari Kawabata, Japan, The Beauitful, and Myself, p71) Konishi Jin'ichi (1991) comments on Myōe's poem, “Even such extremes of expressions are splendid poetry, [though] this cannot possibly be thought waka by ordinary criteria.” (in Cranston, 'Waka Wars', p488)

Rabinovich, p546; Shūchō is the 1st of the 'miscellaneous styles'. Hamanri also discusses various 'defects' of 'regular rhyme' in the first section of Uta no Shiki, none of which is particularly relevant here.

Rabinovich, p547; Kenkei is the 2nd of the 'miscellaneous styles' (after shūchō).

“Riddles like this are fairly rare in Japanese literature. Section 62 of Kenkō's Tsurezuregusa (c. 1330-1332) contains the following example, which spells out the message: 'Longingly [koishiku] I think of you'.” (Rabinovich, p548)

Cranston, GGC, p685. Hiyuka [broadly speaking, 'metaphorical poems'] function in various ways in the Man'yō'shū. Some poems require additional context to decode the 'meaning', usually provided in a koto'bagaki (lit'. 'poem-note', i.e. 'headnote'). Others are based on more straightforward uses of metaphor, further styalised into “encyclopedic sub-categories... such as 'entrusting thoughts to clothing', 'enstrusting thoughts to mountains', and so on... [which] overlap with kibutsu'chinshi.” (Yiu, 'The Category of Hiyuka in the Man'yō'shū', p8-9)

Kokinshū, 'Kanajo Preface' (tr. Rodd, p37-39).

Kojiki, Poem 20 (tr. Chamberlain, Vol. 2, p181; Cranston, GGC, p18).

Man'yō'shū, Book 11, Poem 2762 (Cranston, GGC, p691). Paula Nold Doe: “The 'smile-grass' (nikokusa), may be 'hagi' (keichū) or the 'maidenhair fern' (masazumi). It is similarly used to modify nikoyoka ni (i.e. 'smilingly') in this poem.” (Ōtomo Yakamochi and the Man'yō Tradition of Elegy Vol. 2, p273) Gill translates nikokusa simply as 'young grasses' (i.e. more commonly, waka'kusa). (Mad In Transaltion, p62) I have followed Cranston's translation, who reads “niko in both cases [as] meaning 'soft' [or 'tender'].” (GGC, p691)

Kokinshū, 'Kanajo Preface' (tr. Rodd, p38).

Cranston, GGC, p685. For an extended discussion, see Yiu; “The use of metaphors is common in poems of all categories in the Man'yō'shū.” ('The Category of Hikyuka in the Man'yō'shū', p9)

Rabinovich, p544; Jikigo is the 6th of the 'irregular styles'.

Man'yō'shū, Book 5, Poem 852a (Vovin, M5, p87). See also: Nippon, p242.

This kind of nonsense-verse (lit. 'without-mind') “was composed as a popular literary passtime from the early 8th century, if not slightly earlier still.” (Rabinovich, p542)

Kokin'shū, Book 11, Poem 495 (tr. Rodd, p191; McCullough, p115; Cranston, GOR, p26). This poem was also the inspiration for Iwa'tsutsuji (c. 1676), edited by Kitamura Kigin (1625-1705), one of the earliest known homoerotic waka anthologies, centered on romantic-love between men. While this poem was listed as anonymous in the Kokin'shū, according to Kitabatake Chikafusa (1293-1354) in Kokinshū'Chū (c. 1346), quoted by Kigin, “the poet was Shinga Sōzu (c. 801-879), one of the ten major disciples of Kūkai (c. 774-835). The poem was inspired, legend says, by Shinga's unspoken love for Ariwa Narihira, who's beauty apparently caught the priest's eye.” Kigin adds: “It was this poem that first revealed, like plumes of pampas-grass waving boldly in the wind, the existence of this way of love.” (Schalow, The Invention of a Literary Tradition of Male Love, p4-5)

Rabinovich, p512.

Hitachi no Kuni Fudoki, Poem 7 (tr. Cranston, GGC, p134; Funke, Fudoki, p25; Aoki, Records of Wind & Earth, p60).

Rabinovich, p553-557. Hamanari lists them in reverse order, as the 6th to 10th of the 'miscellaneous styles'. We could continue expanding Hamanari's taxonomy – surely there must be verses in which the whole head and waist contained a 'novel expression' (i.e. tōshin'yōshin, lit. 'new-head-new-waist'), and so on.

Forgotten Poets Presents

Haikai & Haiku, an unfinished miscellany on haiku in English, including poems, translations, histories, theories, et al. Explore the archive . . .

Haiku Thursdays: Back to Beginnings Part 1 - Chōka & Hanka

For the next few weeks we will be exploring the earliest surviving records of Japanese poetry—the Kiki and the Manyō’shū, compiled in the late-600s and early-700s respectively—and the origins of haikai and haiku...

The Origins of Haiku Part 2 - Tanka

Last week we talked about chōka (lit. ‘long poem’) and hanka. This week we are taking a closer look at the history of Japanese tanka (lit. ‘short poem’), the great-grandparent of haiku (and next week, a range of other short poetic forms). Tanka is a 5-line form of poetry, customarily written in 31 kana, in the pattern 5-7-5-7-7. After the poetry reforms…

Haiku Thursdays: Back to Beginnings Part 3 - Katauta, Mondōka, Sedōka, Tan'renga

Last week we discussed the tanka (‘short poem’)—one of the most popular and enduring forms of Japanese poetry—and the week before, the chōka (‘long poem’) and hanka (‘reply poem’)...

Gosh! This will be a long journey. Where to begin? :) Thank you, Dick!

old friends

resurface while

making new ones—

years and miles

irrelevant

Thank you, new friend!